by Steve Miller

Okay, I know… I haven’t blogged in a while. I have been busy with other things and I just haven’t felt the need to take up the bandwidth. That’s all changed. Recent events inspire me. Now, while what’s written on this blog may bore most people to tears, it may be of interest to my children who used to ask, “Where did I come from?”

Many parents dread that question but for reasons other than mine. In the past, I couldn’t answer the question because I truly didn’t know. That’s changed.

Most people can’t imagine not knowing where they spent parts of their childhood or with whom. Who’s mom? Who’s dad? I did more than imagine, I lived it. I was adopted and really didn’t know my biological parents.

Now that I do know from whence I came, I want my children to know. I want their kids to know. More than simply know, I want them to understand that while there might be a definition of a normal family, very few families fit that criteria. In our family, the one that I have just recently discovered, we were so far outside the criteria that we have established a new definition of normal. That’s not such a bad thing.

Deviating from the social norms is what makes a family unconventional. Not operating to the benefit of the family as a whole makes it dysfunctional. While our family may have been dysfunctional in some areas, and certainly unconventional in most, there was also an abundance of love and caring. The loving and caring part wasn’t always apparent. Sometimes you had to look for it. For those who judge, well, first of all, you shouldn’t. If you choose to, you will find plenty of reason to place fault. People do what they’ve got to do to survive. They adapt using the resources available to them at the time. That doesn’t make them bad people.

In our family, most of us have fought our battles, some of us have slain our demons, or at least we have them on a short leash, and we have emerged with a better understanding of where we came from and who we are. We have lost those we love and loved those we found. Our present generation has shed the “dysfunctional family” label. After more than a half-century apart, we’ve finally found each other.

Now, here we are. This is us. But before we talk about us, I’m going to talk about me.

While Leave it to Beaver was playing on 1950s television, the epitome of a healthy wholesome American family, many families were living a much different life. Invaded by alcoholism, marital infidelity, and financial deficiency, my biological family was one of those labeled as dysfunctional.

My parents adopted me at ten years old. Before that, my life as a little kid was spent growing up in the Westlake/Echo Park area of Los Angeles. Today, it’s an area where a bulletproof vest is a necessary fashion accessory. It’s a place where you’ll find more residents affiliated with gangs than credit unions. It’s home to the LAPD Rampart Division where police officers are likely to have more use of force encounters in a week than suburban officers would have in their entire career. It’s an area full of 1920s apartment buildings, home to Korea Town, MacArthur Park, and the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

Westlake wasn’t the worst place for a kid to grow up. The foster care system was. My younger brother, sister, and I made the rounds of several foster homes, some better than others. We also spent some time in the infamous Maclaren Hall.

Maclaren Hall was LA’s answer to the question, “What the hell do we do with all of these delinquent and abandoned kids?” The place was just like a jail, with “perimeter security measures, which include floodlights and a 14-foot chain link fence, topped by five feet of barbed wire,” according to a 1960 L.A. Times article. There was little differentiation between kids who were there for criminal offenses and kids that the city had nowhere else to place. I remember the chain-link fence and the military chow hall where we were lined up and marched in for meals. We were there not because we had done anything wrong but because alcohol had robbed our mother and father of the ability to care for us. It seems that God does visit the sins of the father, and mother, upon the children after all. Mac Hall Article

Mac Hall, as many former residents know it, was a dirty little not-so-well-kept secret. Numerous newspaper articles recorded the horrors of abuse, mistreatment, neglect, and filthy living conditions. Going from there to our first foster home, together, was Nirvana for my younger brother, baby sister, and I.

While some foster homes are loving and nourishing, most of them turn out to be temporary. Even a child knows there’s another chapter when the page turns, and it may not be as loving or nourishing as the last. So, there’s always the anxiety and anticipation of, “What’s next?” and “Where will I go?”. It’s a feeling of powerlessness.

In our first foster home, we found that there was a sort of the caste distinction. The “family” had meals together. The foster kids ate by themselves. If there was a birthday party or other family event we were not invited. There were toys we weren’t allowed to touch. We had an earlier bedtime than the biological children so that the “family” could have their time together. It was very clear to us that we weren’t part of the family and never would be. We were still being warehoused but in much nicer conditions than Mac Hall.

All of the foster families we visited were pretty much like this, some worse, some better. Personally, I wasn’t content in any of them. Not only were the families alien to me, so were the LA suburbs. I learned that if I could find an LA City bus stop and a few quarters, all I had to do was watch for 7th Street and Rampart Boulevard. Then I could find my grandmother’s apartment. It was a seedy, old, nasty apartment building from the beginning of the 20th century, but it was home. I thought that once I was safe on familiar turf, somehow my brother and sister could be retrieved. Not so. Once the child protective services people caught on to my routine and knew where to find me, the time it took to get me back to a foster home became shorter and shorter, and it became harder and harder to escape.

There are some good foster parents out there who open their homes to children they don’t even know out of love and compassion. Some even adopt the children they foster. Personally, I just didn’t have that experience.

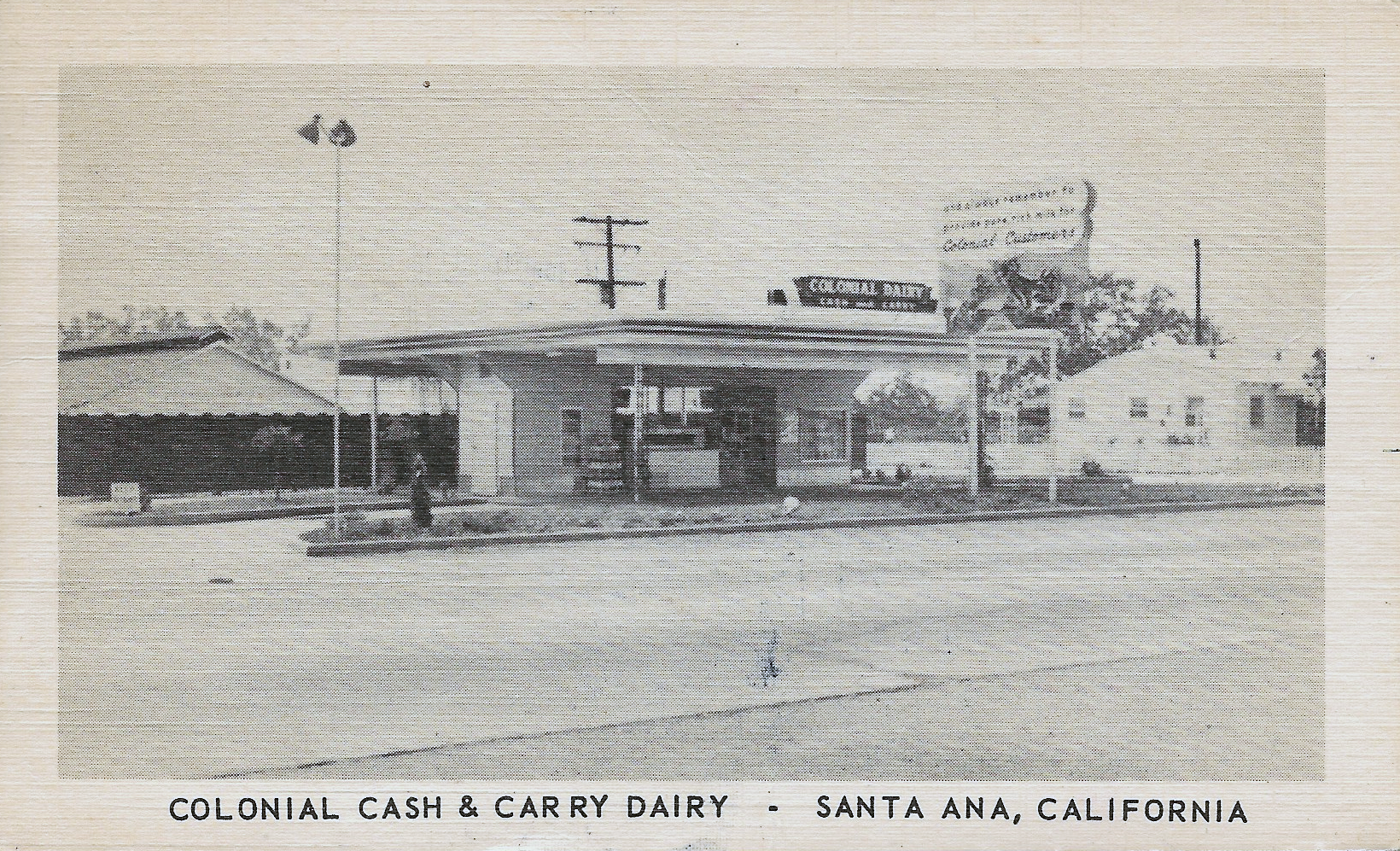

And then there was the dairy.

One day the word came that we were being transferred to a “forever home.” They told us we would have a sister, and be with parents and live on a dairy farm. I was overjoyed. My brother and sister were too young to be overjoyed; they just went along with the program and were happy to follow me to wherever I ended up.

I’m not sure how long I stayed with the dairy family. A few months maybe? But a few months seems like an eternity to a kid. I watched workers milk cows. My brother and I would go to the dairy store and con the clerk out of a half pint bottle of chocolate milk. After all, we were the owner’s soon-to-be-adopted children. But one of us wasn’t.

A few months into my stay at Colonial Dairy in Santa Ana, I was told once again that I would be going to another home. I had heard that before. The difference was that this time I was going, my brother Michael and my sister Nancy would be staying. Apparently, the powers that be didn’t get the message that we were a package deal. The only two family members that I’ve ever known were staying there while I went somewhere else. More than saddened, I was terrified.

I was the oldest. I had always been the protector. Who was going to watch out for my brother and sister while I was being shuttled off to yet another undisclosed destination? What about school? I had never been in any school for more than a few weeks at a time.

As the saying goes, resistance is futile. I gathered my belongings – a few tee shirts that I had since before I entered the foster care system, a couple of pairs of jeans, a toothbrush, all stashed away in a brown paper grocery bag. I remember sitting on a couch, fresh out of the bath and my hair combed, waiting to meet those who would take me to my next destination. I had been in this situation before, just not by myself. My wingman, Mike, wasn’t there to have my back.,

It was late afternoon. I remember seeing a dark green 1954 Ford Customline pull up in front of the house. I was there with Opal, the woman of the dairy farmhouse. Andy, the father, was off somewhere with my brother and sister. The people rang the doorbell, were invited in, and only stayed a short while. If there was a conversation, I don’t remember it. What I do remember is walking out to the green Ford and looking back asking what about Mike and Nancy?

I remember being told that they’re staying at the dairy and being adopted by the dairy people. I was coming to live in a new home – forever. It didn’t register right away. I was skeptical. Once burned, twice shy. I remember turning the corner onto Dunrobin street. Mom pointed out the house, a green bungalow suburban home, very much like the others on the street, and said, “This is your new home.”

“For how long,” I asked.

“For as long as you want to stay here,” she replied. I wanted to believe that so bad that I actually did.

It was dark when we arrived at the house. After skillfully parking the Ford in the garage dangerously close to a two-tone blue 1950 Nash Statesman, the man who would be my father, a big man with arms that look like he could bend steel bars, came with us into the house.

They took me to the room where I would sleep. There was a full-sized bed, a chest of drawers, and a closet. I heard the words, “This is your room. You can decorate it however you want.” Again, I wanted to believe it, so I did.

It took me a day to realize that I had just met the most loving, caring, selfless, and amazing people I would ever meet in my entire life. In a few years, the Millers would officially be mom and dad. I didn’t wait a few years though. I started calling them mom and dad the first day I lived with them. Take ownership. After all, possession is nine-tenths of the law, right?

Over the next few days, mom took me to JC Penney in downtown Bellflower. For the first time in my life, I was able to pick out my shirts, brand new ones, not just wear what someone gave me. I chose the tee shirts that I was familiar with, but mom insisted that I also choose some button-down shirts and explained that I would be starting school soon and I needed to look respectable. I left with bags full of shirts, new jeans, underwear, and a new pair of Buster Brown wingtips.

Within the next week, Dad took me to the barbershop where I received a “regular boy’s haircut.” A part on the side combed up and back in the front. Dad introduced me to everyone in the shop as his son. Not his adopted son, his son. The adoption wouldn’t be final for another three years, but what the hell.

I started school in the third grade, toward the end of the year. I didn’t know how to read. Fortunately, because it was the end of the school year, I was able to skate by using the illustrated “Dick and Jane” readers to stumble through when the teacher called upon me. See Dick Run. See Spot catch the ball. There wasn’t much written work at that grade level, so by the time school was out for the summer, I breathed a sigh of relief. I was afraid that if it was discovered that I didn’t know how to read entering the fourth grade, I would be sent back to the foster system.

Over the summer, I discovered Superman comic books. I picked up some vocabulary through word association. I was able to fake my way through the first few weeks of fourth grade until I was given a written assignment. If you can’t read, you can’t write. Busted!

I was literally in tears when I was kept after school and confronted by my fourth-grade teacher. She showed me a few flash cards with standard vocabulary words for the grade level. I failed miserably. I remember sobbing, explaining that I would be sent back to a life of inconsistency and misery in the foster care system if my parents found out that I couldn’t read. After all, that’s my fault, right?

With the compassion and empathy of Mother Theresa, my teacher proposed a solution. What if I stayed after school every day and worked to catch up? After all, I had a good spoken vocabulary, all I had to do was apply it to the written word. And about my parents knowing that I was at least three years behind grade level in reading? Well, she promised to tell my mother that I was staying late to learn Latin rather than remedial reading.

My teacher didn’t lie to my mom. Mom knew the story from the start, and without letting on that she knew, provided me with an ample supply of reading material. I worked with my teacher after school, sometimes even in her home. I was reading at a sixth-grade level by the end of fourth grade. Plus, I had a vocabulary of about a hundred or so Latin words. Promissis fidem. A promise is a promise. I paid my teacher back by enrolling in Latin classes as soon as I got to high school.

What I didn’t know at the time was that my dad didn’t read either. He would spend hours in front of a newspaper or an open Bible, but he understood very little of what he was looking at. I believe he did that to hide his illiteracy from me so that I would pursue reading. It takes a very strong and resourceful individual to support a family of three as the sole provider without being able to read. I learned that later in life. I also learned to admire those who work hard to achieve what to me seems easy.

Time went on. Once the adoption proceedings were finalized, I got to start Junior High as Steve Miller instead of Steve Mitchell. Actually, I used my middle name, David. All because of some poor excuse for a third-grade teacher who felt she had too many boys named Steve in the class, and that was confusing her.

Listen, lady, if you can’t keep track of a couple of dozen kids, some of whom share the same first name, then you need to turn in your teaching certificate and pursue a rewarding career in the fast food industry.

No, I didn’t think like that then, but I do now. I kept the name David all through high school and finally went back to Steve when I joined the Navy. It was just in time to start hearing quips about the Fly Like an Eagle guy. The lesson I learned: I will never again let someone take something from me just to make it more convenient for them.

Meanwhile, life was good at the Miller’s. I finally belonged somewhere. They made sure that I had everything a red-blooded American boy should have. A red Radio Flyer wagon. A bike. A dachshund. Piano lessons. Life was good. I didn’t forget about my brother and sister. I frequently asked about them. I was told that they were doing great in their adoptive home too. I wanted to believe that too, so I did.

To be continued…

I love you uncle Steve. Sounds like you and I shared the same difficulties in reading. I can’t tell you how much respect I’ve got for you. The thing I’ve come to know about our family is we may all have our issues but we all have a good heart. You should write a book. I think your a awesome and I’m super proud that we’re blood. Love you Jen