By Steve Miller

Ever since my fourth-grade teacher taught me Latin in a pretext for teaching me to read, I have been intrigued with language. I have always been interested in the origin of words. It’s not enough for me to learn a new word, I need to know how it evolved into our language as well.

I find names equally intriguing. Sometimes they give you a clue as to where a person comes from or even a clue to their physical appearance. A common name like mine is pretty nondescript. I always wanted to have a last name like Steve Nakamura so that when people met me in person, they would be shocked by my Caucasian appearance.

While doing family research, I found out that my birth mother’s third husband was Jewish. His name was Ray Berman. He fathered my half-brother and two of my half-sisters. I still haven’t found any specifics for this man, other than his name and a few pictures from the family archives.

For a long time, there was some debate as to whether my original surname should be Berman or Mitchell. I was conceived during the transition from my birth mother’s second and third husbands. Neither took ownership. James Allen Mitchell finally agreed to sign the adoption papers, thereby admitting paternity, when he was given the guarantee that there would be no liability on his part. Smart man.

However, 67 years later, a DNA test would prove that I was predominate of British heritage, thereby making me a Mitchell, at least from the choices that were available.

For the six decades that I was in cultural limbo, I often pondered the choices. If I was a Mitchell, I was likely English. If I were a Berman, I was either German or Jewish. The difference between being German and English is pretty low key. Being Jewish, however, is a big deal because it’s non-secular.

If I were Jewish, I would be supposed to be going to synagogue instead of church. I would be entitled to Israeli citizenship. And, according to the Old Testament, I would be one of God’s chosen people – although the good lord knows that during my existence here on Earth, I have done plenty of things to piss Him off. So, chances are, He would have chosen someone else. As it turned out, He did.

Berman versus Mitchell. It didn’t matter because I was a Miller. But while I was searching, the question crossed my mind as to why Jewish names are so recognizable. Many of them sound German, and that’s because they are.

I knew that Jews were forced out of their homeland and settled worldwide, mostly in Europe. I have always thought that maybe they Germanized their last names so as not to stand out, just like American immigrants changed their European sounding names to be more pronounceable and acceptable in the American culture. That’s wasn’t the case.

Now that I know I have Jewish relatives, even though I have no Jewish blood myself, makes it even more imperative, just to satisfy my own curiosity, that I answer the question of what makes Jewish surnames distinct.

Today, last names seem like a necessity. That was not always the case. In fact, last names first were used well into the development of Western civilization. Even then, the surname, (meaning, the name of he who sired you) was a new idea for the everyday Joe.

Surnames used to be exclusive to those of nobility. People who weren’t nobles simply weren’t considered important enough to merit last names. Now it’s the other way around. If you become noble enough to acquire celebrity status, e.g., Madonna, Bono, Adele, Twiggy, Cher, you don’t need a last name because everyone knows who you are.

In the years before 1787, most Jews used patronymics. That’s a name derived from the name of a father, typically by the addition of a prefix or suffix.

Jewish names are appended with the Hebrew ‘son of’, such as Moshe ben Yosef (Moses son of Joseph), or ‘daughter of’ (Rachel bat Laban). In Jewish legal documents, and in the synagogue, last names are still not used today.

Other cultures used patronyms too. For example, in English, Johnson is John’s son, in Irish O’Brien is the son of Brien, and in Russian, Ivanovich would be Ivan’s male offspring. I guess if Ivan had two sons, they would have to fight it out – or, use a distinctive first and last name like Igor Ivanovich.

Anyway, in 1787, the Austrian emperor issued a decree forcing Jews to adopt German surnames. This law was the first legislation that mandated the use of a permanent last name for Jewish people. Surnames facilitated the tracking and taxing of Jews. Incidentally, the American government initiated Social Security for the same reason.

Many Jews were simply assigned surnames based on their superficial appearance. That’s why Schwartz (black), Weiss (white), Gross, (big), and Klein (small), are common Jewish names. Some were common objects like Stein (stone), Blum (flower).

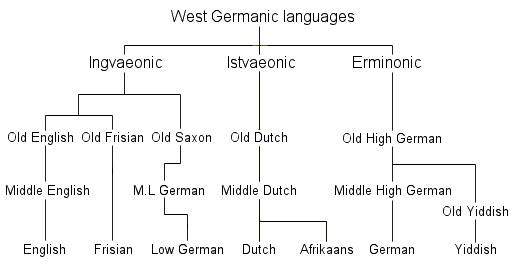

Yiddish is a language used by Jews in central and eastern Europe before the Holocaust. It was originally a German dialect with words from Hebrew and several modern languages. This is much like the Pidgin English, a combination of English, Polynesian, and several Asian languages, which is spoken in Hawaii.

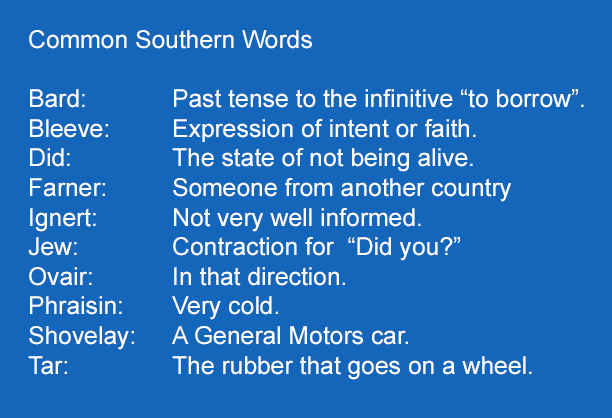

If you’ve ever been called a schmuck, (in English that would be “prick”) you’ve heard Yiddish. Shlemiel refers to a clumsy person, also called a klutz. Schlimazel is a person who always seems to have bad luck. Schlemiel! Schlimazel! If you’ve ever watched Laverne and Shirley or played hopscotch, you’ve heard Yiddish.

So, the last name “Schwartz” doesn’t only mean “Black” in German, it also means “Black” in Yiddish. “Zuckerberg” literally means “Sugar Mountain” in the two languages as well. I will never look at that Facebook dude the same way ever again.

You’ve probably spoken Yiddish too. If you’ve ever referred to someone’s butt as a tush, it’s a derivative of the Yiddish work tuches. If you’ve called someone a klutz, it’s the Yiddish word meaning “block of wood.”

Okay, so how come so many Jewish names sound Polish or Russian? The 1987 Austrian edict was so successful that when Napolean took over most of Europe, he issued a decree in 1808 that required Jews outside of Germany and Prussia to adopt surnames as well. The majority of those Jews took on Polish last names.

Towards the early 19th century, after the partition of Poland, Russia acquired a large number of Jewish territories and mandated the use of surnames, which were, naturally, Russianized Hebrew names. This is the reason for common German, Polish, and Russian sounding Jewish last names with suffixes like -stein, -berg, -witz, -ski, -sky, -man.

Remember, all names that sound Jewish are not necessarily Jewish, but are simply German, Polish, and Russian names; sometimes even Korean. There are very few pure Hebrew surnames, like Levy, Israel, Moss, and Cohen.

Now, here’s the real surprise: According to the 1990 US census, Miller is the third most common surname among Jews in the United States (after Cohen and Levy). Maybe it was fate that I have a Jewish surname after all.

The American flag is something worn by heros and those in service to their country, not inmates. Many of those held are immigrants, legal or otherwise, from other countries. They’re not American citizens and to make them wear our flag is a misuse of the flag. Unless they’ve been convicted and sentenced, they’re being held for trial to determine if they’re guilty. As such, making them wear the flag of a country to which they bear no allegiance is not only wrong, it’s a denial of their due process.

The American flag is something worn by heros and those in service to their country, not inmates. Many of those held are immigrants, legal or otherwise, from other countries. They’re not American citizens and to make them wear our flag is a misuse of the flag. Unless they’ve been convicted and sentenced, they’re being held for trial to determine if they’re guilty. As such, making them wear the flag of a country to which they bear no allegiance is not only wrong, it’s a denial of their due process. In the past, Arpiao had the American flag painted inside the cells in his jails. He then dared any inmate to deface it, threatening them with charges of an crime if they did.

In the past, Arpiao had the American flag painted inside the cells in his jails. He then dared any inmate to deface it, threatening them with charges of an crime if they did.