by Steve Miller

For an adopted kid in a great home, biological heritage doesn’t matter. And then it does. Adopting older children makes a radical and notable change in their life versus adopting an infant who isn’t aware that they were adopted — at least not until they become aware.

In some cases, when a child finds out that their parents aren’t really their parents, there can be a sense of betrayal. There can be confusion, resentment, and chaos. That wasn’t a problem for me; I became aware of my radical and notable change as it occurred.

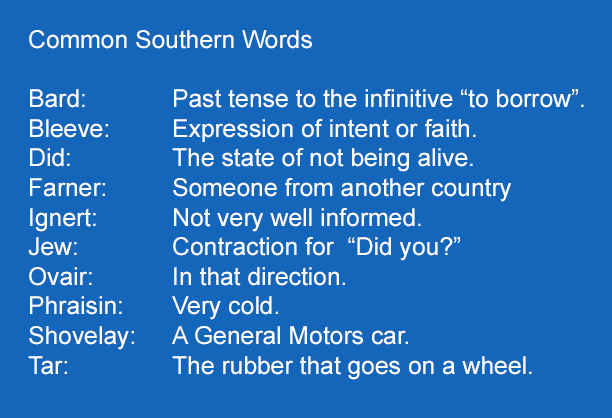

As I blended in as part of the Miller family, I took on their traits. My acquired southern accent got bad enough that the school sent me to speech therapy. Once they talked to my mother in person about my progress, they figured it out and quit wasting their time. How was I to know that “over yonder” wasn’t a precise location or that “that” was always followed by “there”? And making two syllables our of one-syllable words seemed to me like a sophisticated way to pronounce them. For example, a fo-wah comes right before five. The window was a “winder”. Had I grown up speaking southern from the start, I would have probably been okay, but the hybrid California/Tennessee pronunciation of words didn’t cut it in school.

I wanted so much to be like my parents that during the first year, I tried to emulate a lot of what they did. I was elated when my last name was officially changed to Miller, and I didn’t have to answer stupid questions like, “How come you and your mom and dad don’t have the same name?” Nevertheless, part of me always questioned who I really was. The older I got, the more I wondered about it.

I always had a feeling of exclusion when people would talk about their nationality. “I’m German and Irish.” or “I’m Spanish, Portuguese, and Native American.” When it came to be my turn, it was, um, well, quiet. Then one time, with a burst of courage and sarcasm, I said, “I don’t know what nationality I am. I was adopted. For all I know, I could be a space alien with superpowers that I haven’t discovered yet.” It went over well, generated some laughter, and I started using that line a lot from then on. Secretly, I still fantasized about being an heir to the Romanov dynasty. After all, they never did find Anastasia.

What you don’t know can hurt you. Maybe not physically, but it puts you in a position where you need to write your own story. For example, I wondered if there was something wrong with me that I didn’t stay with my biological parents. But then it couldn’t be just me, because my brother and sister were given up too. So, what I resigned myself to believe was that there was something that my mother and father wanted more than children. That turned out to be true, at least partially true.

Somehow my birth mother found herself in a situation where she couldn’t support the three children she had in her custody. I haven’t discovered what that reason was. Recently, I found that she too was adopted and found herself in a strict home that wasn’t anywhere as nourishing or loving as mine. She hated it. So, it wasn’t like she had any delusions about adoption.

Until recently, I had a lot of resentment toward her about being given up. How could she? I never considered that the choice to part with us was probably gut-wrenching and emotionally draining. I never thought of it as a gesture of kindness, a sacrifice, or a gift of mercy. I do think that way now.

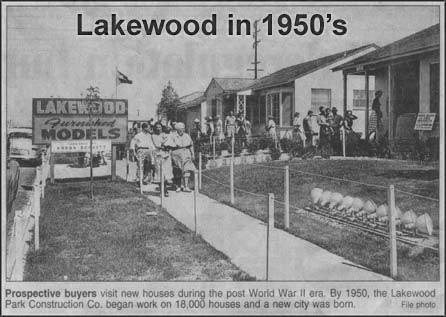

All in all, I was satisfied with my situation as a child growing up in the suburbs. I envied no one. I had everything that a kid could want. I had it better than the Beaver because I didn’t have a dad who made me listen to these metaphorical right-versus-wrong morality speeches each time I did something wrong. My dad handled reprimands quickly and efficiently. It was better that way, and it must have worked because I didn’t get in nearly as much trouble as the Beaver did.

I didn’t miss much of the great 1960s Southern California experience growing up. Dad had the same job at the General Motors plant from the time he and mom were married until he retired. Mom was a housewife when the title still one of honor and respect. Breakfast and dinner were always at the same time. There wasn’t any luxury, but there weren’t any deficiencies either. You don’t get more “normal” or typical than our family was. Well, maybe the Cleavers were.

I didn’t miss much of the great 1960s Southern California experience growing up. Dad had the same job at the General Motors plant from the time he and mom were married until he retired. Mom was a housewife when the title still one of honor and respect. Breakfast and dinner were always at the same time. There wasn’t any luxury, but there weren’t any deficiencies either. You don’t get more “normal” or typical than our family was. Well, maybe the Cleavers were.

Some days the fact that I was adopted didn’t even cross my mind. And then other days it was all I could think of. I had a brother and a sister. And, as it turned out, another brother and three more sisters that I didn’t even know of at the time. I would see people out in public and sometimes wonder if I had just been in proximity to a relative.

I didn’t realize how far out of their way my parents went to make sure that I had not only what I needed but what a middle-class southern California kid was supposed to have. A bike, and eventually a car. I got a small, portable Remington typewriter for Christmas, which I eventually wore out. I got piano lessons and a giant upright piano on which to practice. Not only did I get the basics, but I also got a lot of extras, most of which I took for granted at the time.

Everything that I got required some degree of sacrifice on the part of my parents. What I learned later is that sacrifice isn’t always material or financial. Sometimes sacrifice comes from deep within one’s heart.

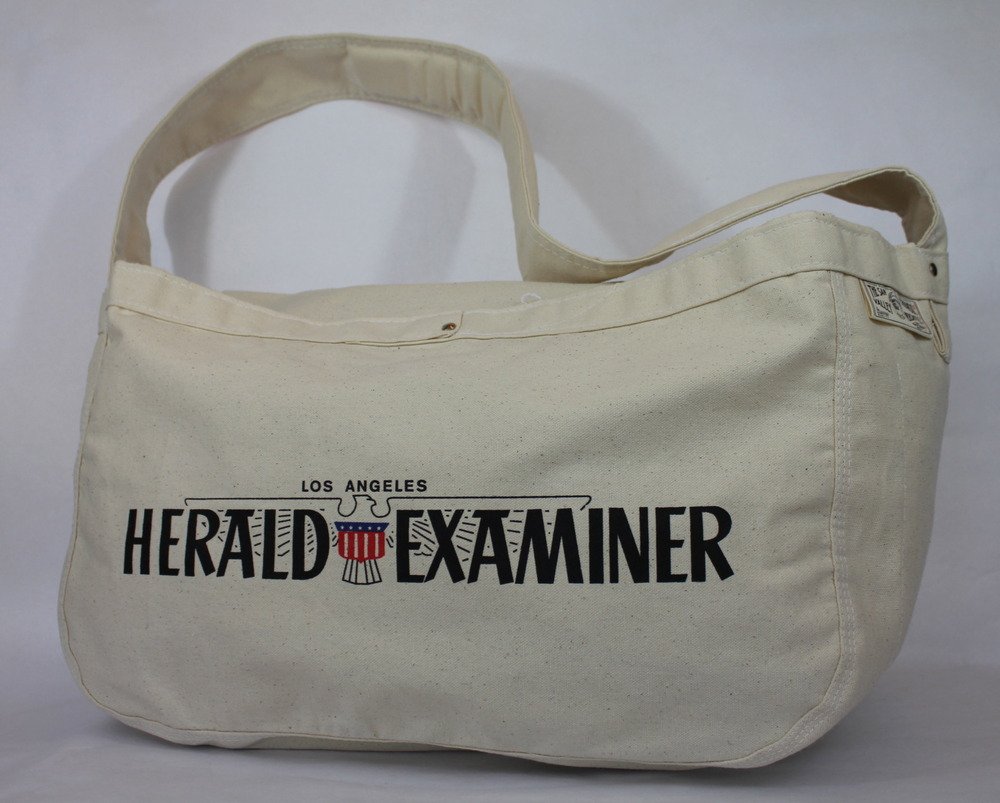

When I was about 12, in 7th grade, I wanted a paper route. Other kids had them, and they were making a fantastic profit for doing something that was fun – riding a bike and throwing papers. My allowance at the time was a couple of bucks a week. A paper route could get me as much as ten to fifteen dollars a week depending on how many customers I had.

When a route became open in our neighborhood, I begged, pleaded, lobbied, and negotiated until I got permission to apply for it. Not only did I get that route, I eventually got a route right next to it. There were so many papers to deliver after school that I had to make several trips back home each afternoon to replenish my saddlebags. On Saturday and Sunday, the paper was four times as big and had to be delivered in the morning. I would hear the “thud” as several bundles of newspapers were dropped off in the driveway by the delivery truck. Most mornings, mom would get up with me to help insert the sales ads and put on rubber bands or plastic bags depending on the weather.

Each trip, she would stand on the porch and watch as I rode off into the predawn darkness to deliver my route. What I didn’t know at the time was that her 13-year-old son from her first marriage had been hit and killed by a drunk driver while delivering the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, the same paper that I was delivering.

She could have easily told me no, you’re not getting a paper route. Who would have blamed her? I can’t imagine the kind of angst that she felt each time she saw me ride my bike off into the darkness on a rainy Sunday morning. It wasn’t about the money – she could have just given me what I would make on my paper route. No, it was about me being like everyone else, doing things that I wanted to do – she wanted to make sure I had that experience. As I said, sacrifice sometimes means giving up a piece of your heart.

Forgiveness is like a sacrifice because to accomplish it you have to give something up. In fact, “give up” is the meaning of both words. In the case of forgiving someone, you have to give up the desire for vengeance or resentment. I realize now that both my biological mother and my adoptive mother made sacrifices, just in different ways.

Something caused me to embark on this journey to find my past. I couldn’t shake the curiosity about my heritage. Friends and family told me over and over I should look into at least finding my siblings.

When it became possible to discover my nationalities without much effort or expense, I took the leap, spit in the bottle, and waited. When the results came back from Ancestry.com, I was surprised. Now I belonged. No longer was I a space alien with undisclosed superpowers. I was from somewhere on Earth just like everyone else.

The results proved that I am mostly British, some German, and a small part from various other places in Western Europe. To celebrate my new status of being included, I bought a British flag. I was still a Miller though, by choice. Not mine, theirs. Their choice was the single most significant event in my life.

The DNA test proved that biological father was wrong when he disputed paternity. Otherwise, I would have been part Jewish like my half-brother. I can understand why he may have had his doubts.

Now that I have confirmation that I was from planet Earth, I want to know more about where I came from and what led up to me being who and where I am. I want to know about my biological parents and their history. I don’t want to stop there. I want to go back as far as I can and find out what I can about those who share my DNA.

My past is now present, but I’m going to save that story for next time.